I’m very excited to have Shana Mlawski, author of Hammer of Witches, here today. Hammer of Witches, a fantasy set during Columbus’ westward voyage, is fantastic and unique and I highly recommend it!

I’m very excited to have Shana Mlawski, author of Hammer of Witches, here today. Hammer of Witches, a fantasy set during Columbus’ westward voyage, is fantastic and unique and I highly recommend it!

But Shana isn’t talking about her new book today (which you should totally read!). Shane also blogs over at Overthinkingit.com, which is an awesome website where pop culture is looked at through a variety of lenses (mostly critical). Plus, she includes infographics in many of her entries and I have an infographic obsession! So today Shana is here to talk about the intersection between her life as a writer and her life as a pop culture critic. And it’s a fascinating read!

*********************************

THE CRITICS AND THE CRITICIZED: OR, SHOULD WRITERS WRITE REVIEWS?

What is the relationship between authors and critics? Should writers adjust their work to please reviewers, and what happens when critics try to write fiction themselves?

I’ve been thinking a lot about these questions lately, and not just because my first book, HAMMER OF WITCHES, was recently put out into the world to be judged. (Irrelevant side note: The reviews are pretty good.) The thing is, *I’m* a critic. Some of you might know me not for this book but for my pieces on OverthinkingIt.com, a blog full of pop culture criticism. During my tenure as an Overthinking It staff writer, I’ve criticized the idea of strong female characters, the philosophy behind Christopher Nolan’s Batman films, books that have the word “daughter” in the title , and every episode of LOST. If I have any fame whatsoever, it comes from being a critic.

But what happens when someone who has spent her life criticizing other people’s work tries to create her own works of art?

In my case, the answer to that question is, “She sits down and has a long think.”

FIVE TYPES OF INTERNET CRITICISM

Criticism can hurt. We’re not supposed to say that, because we’re supposed to have thick skin, and the millions of rejections I’ve gotten over the years have certainly thickened mine. Nevertheless, criticisms hurt, and when they do I feel guilty about all the times I’ve criticized other people’s work. Then I vow never to criticize again.

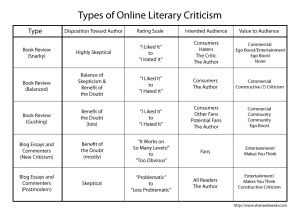

Silly vow, ain’t it? Criticism is fine—at least, some kinds of criticism are, sometimes. And, yes, there are different kinds of criticism. I’m no literary theorist, so instead of quoting Michel Foucault or Harold Bloom, I made a chart:

As you can see, I’ve listed the five main types of literary criticism we see on the Internet. The first three are reviews you see on Goodreads, Amazon, book blogs, Roger Ebert’s old website, and so on. Snarky, balanced, and obsessed-fan reviewers write for different audiences and for different reasons. Some have commerce in mind (“I want to help people decide whether or not they should buy this”). Some have community in mind (“I want to share my love with other fans and bring new people into the fandom”). Some have entertainment and their own ego in mind (“I’m want to make people laugh”), and some have the author’s ego in mind (“I’m going to cut her down to size”/“I’m going to show her how much I love her”).

In those first three kinds of Internet criticism, star ratings count. But there are two more types of criticism where star ratings are irrelevant. Writers of Internet-based New Criticism assume the reviewed work is great and everyone already agrees it’s great. Here, the critic’s job is not to judge but analyze and deepen the fans’ reading of the text by noticing symbols, themes, allusions, and other literary techniques. Most blog posts about Mad Men fall under this heading. The critic usually assumes that everyone agrees Mad Men is amazing and that everything in each episode was placed there with care by Matt Weiner and the other writers. The purpose of the review is to gather around the digital watercooler and pick apart why one episode was named “The Collaborators,” why Don Draper was reading Dante’s Inferno, and why it was symbolic that Betty dyed her hair black. In this way, the critic deepens our enjoyment of the text.

The last kind of literary criticism is the postmodern kind. Here, critics can view the text from a political angle. They may question Game of Thrones’ imperialism or praise its feminism. They might criticize Girls for its overwhelming whiteness or The Big Bang Theory for the way it treats autism. These last two types of criticism are the kinds I write for Overthinking It.

WHAT’S AN AUTHOR TO DO?

Once I realized I was conflating five different things and calling them all “criticism,” my question changed from, “Should I stop writing criticism now that I’m an author?” to “Which kinds of criticism should we write, and how?”

The answer depends on who we’re trying to help.

I’m an author now, so mainly I want to help other authors, so I’m going to try really, really hard not to write any more snarky reviews. These reviews can be a blast to write and read, and they might help someone make a purchasing decision. But they’re often unfair. Strip everything away from a snarky review, and what’s left is, “This text is bad and you should feel bad” Except, “This text is objectively bad” usually means “I didn’t like it for some personal reason.” The reason can be innocuous—e.g., the writer used the present tense and you hate the present tense—but sometimes it’s based on prejudices and cruelty. Some reviewers approach certain books with extreme skepticism and give their authors no benefit of the doubt because of the author’s race, gender, sexuality, age, or some other factor that has nothing to do with his or her skill as a writer. This kind of criticism needs to be called out by other readers. We reviewers also need to consider our own unconscious biases when we start to unload the snark on a possibly-undeserving author.

What about fair and balanced reviews? They seem more useful to authors, because they’re said to offer constructive, rather than destructive, criticism. However, in my experience, these reviews aren’t really constructive to authors at all, because they tend to contradict one another. One reviewer loves the main character; one hates him. One loved the prose; one hated the prose. One was moved to tears; one felt nothing. Unless 90% of the reviewers make the same exact comment, this type of criticism will not help an author improve his or her craft. But fair, well-written reviews help authors in a different way. Reviewing a book puts it on readers’ radar, so your balanced review acts as a form of advertising. So if you’re a reader and you want to support an author, write a fair review for one of the major websites. It helps!

As for gushing reviews: they’re nice for a quick ego boost and a smile, but they won’t help me improve my craft, either. (I appreciate the ego boosts, though! Thanks!) That said, I’ll never give up writing gushing reviews myself. Sometimes you need to express your love for a work of art. Unrelated: Has everyone here watched Slings and Arrows yet? OMG it’s amazing! Funny, clever, wonderful for Shakespeare fans and even more wonderful for artists. Mark McKinney’s in it! And Rachel McAdams! It’s on Netflix! Go watch it now!

Writing New Criticism is fun, and so is reading it. I can’t imagine analyzing the symbolism of a writer’s work actually helps the writer improve his or her craft, but it helps readers enjoy the text more, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Anyway, my editor at Overthinking It will flip out at me if I give up this type of criticism. I promised I’d do video recaps of Game of Thrones and Mad Men every week.

The one type of criticism we should never give up is the postmodern kind. I can’t. I can’t shut off my brain when I’m reading or watching something. Let’s say I’m watching a comedy, for instance, and there’s a rape “joke.” I’m not NOT going to notice it. It’s not that I’m looking for sexism; it’s that the movie features some sexism. I’m going to point it out in my reviews in the hopes that writers stop writing sexist things and that audiences stop enjoying them. This type of criticism can truly be called constructive, as long as it’s fair. I like to give authors some benefit of the doubt and assume they’re at least trying to write in good faith. After all, criticizing is easy. Creating is hard.

What do you think? Should critics risk becoming authors? Should authors risk writing criticism? If so, what kind? I’d love to hear what you have to say in the comments.

Filed under: author engagements, interviews | Tagged: Big Bang Theory, hammer of witches, historical fantasy, Michel Foucault, new criticism, shana mlawski |

[…] Tuesday, May 7: The Reading Zone – Shana on Being a Reviewer and Being Reviewed – Read today’s guest post here. […]

[…] is Should Writers Write Reviews? Shana Mlawski’s answer is one I wholeheartedly agree […]